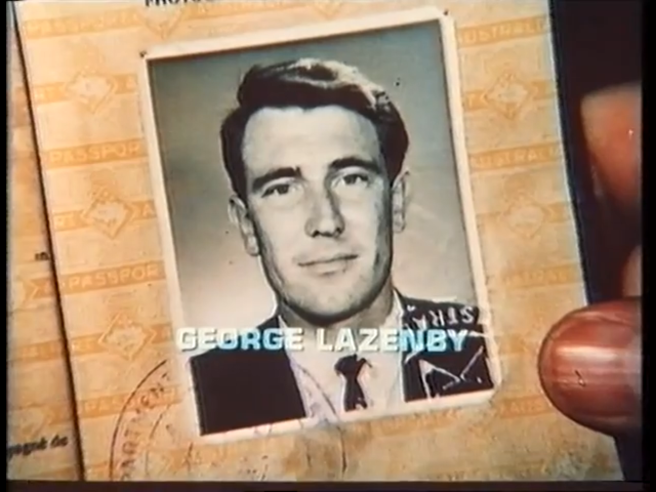

This post is part of the Rule Britannia Blogathon run by Terence Towles Canote at his site A Shroud of Thoughts. My contribution is about a film co-written by two men who are both really only known for having one big famous movie on their CV’s. Leading man George Lazenby of course replaced Sean Connery as James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969, Peter Hunt) before quitting the franchise shortly after the film’s release. Cy Endfield directed Sunday afternoon favourite Zulu (1964). Both of these films present a positive image of Britishness. Bond as the ultimate male fantasy, and Stanley Baker and Michael Caine’s army officers maintaining their stiff upper lips in the face of insurmountable odds.

This post is part of the Rule Britannia Blogathon run by Terence Towles Canote at his site A Shroud of Thoughts. My contribution is about a film co-written by two men who are both really only known for having one big famous movie on their CV’s. Leading man George Lazenby of course replaced Sean Connery as James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969, Peter Hunt) before quitting the franchise shortly after the film’s release. Cy Endfield directed Sunday afternoon favourite Zulu (1964). Both of these films present a positive image of Britishness. Bond as the ultimate male fantasy, and Stanley Baker and Michael Caine’s army officers maintaining their stiff upper lips in the face of insurmountable odds.

Universal Soldier undercuts this view of violent heroism with a meandering tale of a mercenary who gets involved with the anti-war movement in London. Taking it’s title from the Buffy Marie Sainte protest song Universal Soldier is clearly semi-improvised with the thematic concern driving the narrative.  The film however flopped. Universal Soldier didn’t come out until a year after it was made and Lazenby claims to have only seen it once. It might be a mess but it feels more pertinent than ever due to parallels with post-60s’ Britain and where we are now. It’s engagement with the emerging counter-culture makes it an interesting snapshot of a particular time and place and in that respect it’s one of the great London as location movies. It’s also clearly a work of autobiography. This is a film about a man walking away from everything people expected of him and trying to find his own identity.

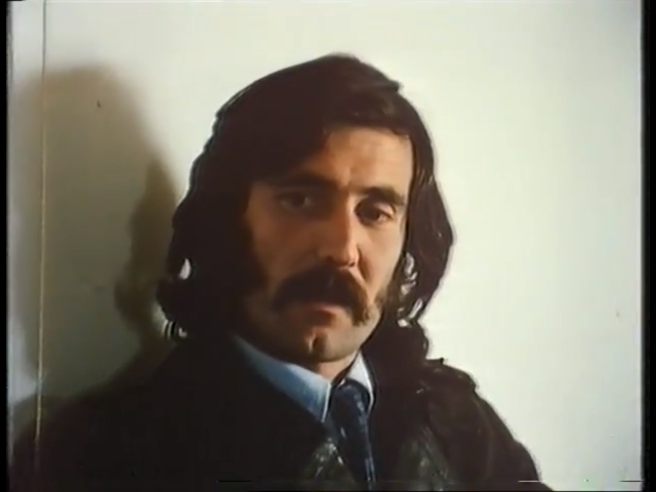

The film however flopped. Universal Soldier didn’t come out until a year after it was made and Lazenby claims to have only seen it once. It might be a mess but it feels more pertinent than ever due to parallels with post-60s’ Britain and where we are now. It’s engagement with the emerging counter-culture makes it an interesting snapshot of a particular time and place and in that respect it’s one of the great London as location movies. It’s also clearly a work of autobiography. This is a film about a man walking away from everything people expected of him and trying to find his own identity. This departure from the Bondian image is emphasised in the opening scene which shows the former 007 walking through Heathrow arrivals now sporting long hair, a 70s’ porntache, and dressed in a full-length black leather jacket. It’s quite the look and it suits him. While Bond films make travel seem glamorous Universal Soldier presents the unfriendliness of the British customs official. Racially profiling a black man, pulling a hippy aside for a cavity search, and dealing brusquely with visitors from Commonwealth countries. The whole film develops this theme. This isn’t the London of the Singing Sixties but a dull grey place with miserable people protecting their drab little island from outsiders.

This departure from the Bondian image is emphasised in the opening scene which shows the former 007 walking through Heathrow arrivals now sporting long hair, a 70s’ porntache, and dressed in a full-length black leather jacket. It’s quite the look and it suits him. While Bond films make travel seem glamorous Universal Soldier presents the unfriendliness of the British customs official. Racially profiling a black man, pulling a hippy aside for a cavity search, and dealing brusquely with visitors from Commonwealth countries. The whole film develops this theme. This isn’t the London of the Singing Sixties but a dull grey place with miserable people protecting their drab little island from outsiders. Lazenby plays Ryker, a world weary mercenary involved in a Mark Thatcher style plot to overthrow an African regime. There is an absurd sequence where the group watch a promotional video made by an arms manufacturer set to the music of the Monty Python theme.Then the group meet in the countryside to test weapons and plan their campaign. There’s a food hamper and flasks of tea. It’s like a picnic with guns. They test that most ingenious and silliest looking of British inventions, the hovercraft as a potential sea and land attack vehicle. Yet Ryker’s having these wee flashbacks to campaigns he’s been involved in. Something’s not right with him and these feelings are exacerbated when his friend’s dog playfully chases after a target thrown into the air and jumps directly into the line of fire.

Lazenby plays Ryker, a world weary mercenary involved in a Mark Thatcher style plot to overthrow an African regime. There is an absurd sequence where the group watch a promotional video made by an arms manufacturer set to the music of the Monty Python theme.Then the group meet in the countryside to test weapons and plan their campaign. There’s a food hamper and flasks of tea. It’s like a picnic with guns. They test that most ingenious and silliest looking of British inventions, the hovercraft as a potential sea and land attack vehicle. Yet Ryker’s having these wee flashbacks to campaigns he’s been involved in. Something’s not right with him and these feelings are exacerbated when his friend’s dog playfully chases after a target thrown into the air and jumps directly into the line of fire.

Ryker begins to drift away from the cause, a break that’s emphasised in a scene directly referencing Bond and Lazenby’s own social activities. In a scene cut from the original release of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service but eventually restored for DVD Bond reads a copy of Playboy while breaking into an office. Lazenby’s own regular hangout in London was the Playboy Club and maybe this is him saying goodbye to the trappings his brief moment in the spotlight brought him.

There’s a low-rent comedy version of the car chase often found in Bond movies where an unwitting minor member of law enforcement gives pursuit without realising they’re after a secret agent. Here two hapless policemen pull Ryker and his partner over for a minor traffic offence only for them to speed off through the countryside because they have no papers and can’t risk being identified. “We’re chasing a mad bastard…”

Lazenby and Endfield meant the film to be a series of moments and wrote a shadow script about gunrunners to fool the producers into backing the film. Really the film is about Lazenby, observing him as he eats in a dodgy looking cafe in the West End or wandering through Soho at night to a prog-rock soundtrack. After an encounter with a cab driver in which he accidentally offends the Little Englander’s sense of national pride he’s dropped off in Portobello Road because the driver assumes he’s a hippy.

London really gets under Ryker’s skin. He breaks off all contact with his fellow mercenaries and starts hanging out with a bunch of student revolutionaries (including Germaine Greer). Their ideas begin to rub off on him and he double-crosses his accomplices by disposing of the guns. But mercenaries don’t forget any more than Hollywood producers do if you piss them off and Lazenby’s only hiding in a wee flat in Kensington with a Marianne Faithful lookalike.

Lazenby claims he quit Bond on the advice of his then manager Rohan O’Reilly (who appears in the film as an anti-apartheid campaigner). The days of Establishment figures like Bond and conventional forms of cinema were on the way out and the counter-culture would go mainstream. In retrospect this seems like bad advice but at the time it seemed plausible. This was the era of the Angry Brigade and other left-wing anarchist groups in Europe beginning to make their presence known. Same with movies. In the US there was Easy Rider (1969, Dennis Hopper) while in Italy directors like Bertolucci and Francesco Rosi were making left-leaning political thrillers. Lazenby & O’Reilly just didn’t figure out that the Establishment absorbs new ideas and always reasserts itself in the end.  You can tell they went into Universal Soldier without an ending because the big finale is a fight sequence on a motorway lay-by. The antithesis of Bond in every way especially as Ryker repeatedly tries to walk away from the fight. There’s a sense of finality about the film. It was Cy Endfield’s last movie and effectively ended any hopes Lazenby had of maintaining an A-list career. The thriller aspects feel incidental. They’re clearly not interested in making an action film but trying to do a European style art movie. It doesn’t quite hang together, but it’s an effective mood piece that seems to channel the restlessness of its leading man.

You can tell they went into Universal Soldier without an ending because the big finale is a fight sequence on a motorway lay-by. The antithesis of Bond in every way especially as Ryker repeatedly tries to walk away from the fight. There’s a sense of finality about the film. It was Cy Endfield’s last movie and effectively ended any hopes Lazenby had of maintaining an A-list career. The thriller aspects feel incidental. They’re clearly not interested in making an action film but trying to do a European style art movie. It doesn’t quite hang together, but it’s an effective mood piece that seems to channel the restlessness of its leading man.